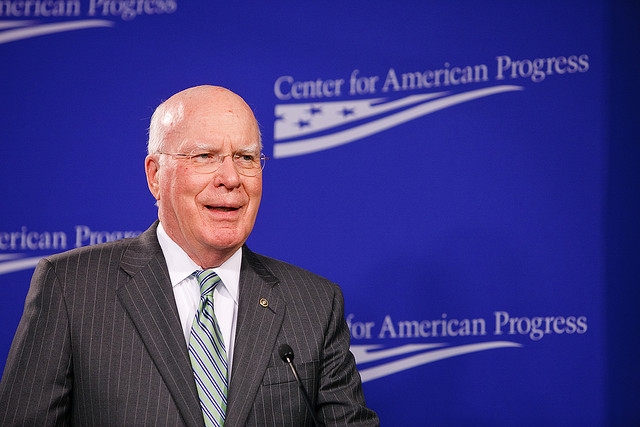

IN AN ERA where economic policymaking skews strongly toward free-market forces, London School of Economics professor Anthony Atkinson—one of the world’s top academics on inequality and income distribution—still stands in defense of government intervention to redress the lopsided state of wealth that prevails in so many countries today.

In fact, Atkinson’s new book, Inequality: What Can Be Done?, reads like a manifesto for old-school, left-wing politics and a reaffirmation of Keynesian ideas: healthy minimum wages, employment assurances, a capital endowment for young adults, tax discounts for the needy. It’s all there and more, with novel twists.

Inequality: What Can Be Done? by Anthony B. Atkinson

Inequality: What Can Be Done? by Anthony B. Atkinson

Technology also factors into Atkinson’s treatise. Among other ideas, he proposes government policies to help assure that technological change encourages innovation while also increasing employment and “emphasizing the human dimension of service provision.” We sat down with Atkinson for a closer look at how he views technology’s influence—good or bad—on wealth.

What excites you most about technology and where we’re heading with it?

Thinking back over my working life, the thing that technology has changed the most is removing very hard manual labor and a lot of very routine labor. Jobs are now much more interesting than in the days when half the population did things that were extremely tiring or boring. There’s no doubt IT has opened up to scientific work enormous horizons that were not possible when I started. If I was a young economist today, that’s what I would find very exciting.

Have we removed the manual labor or are we just moving it around the world to a different place?

A friend of mine is a boat builder, and he said when the timber arrived in the yard everyone in the yard used to stop work and lift their timber off the lorry. Now a guy does it with a forklift truck. That’s technology. One forgets that people came home from work pretty well exhausted. Now when they come home from work they’re fed up, but they’re not drained.

Another good example is designing robots for the paint shop. Painting cars was hard work but it’s also extremely unpleasant and dangerous—lots of noxious fumes. We’ve done away with some unpleasant work.

What worries you about technology?

I’m concerned rather than worried. We should actually make sure that it is distributed fairly and benefits us both in terms of workers and consumers.

Is technology making us a more or less equal society?

I don’t think there’s a bias in it. I think it’s really how we use the technology. It’s a question about who makes the decision as to how it’s used and the kind of products in which technology is embodied, and the way we distribute those. For example is it being used to develop personal services in some way, new forms of leisure services?

One has to ask what is the context in which it’s being developed. The context is one where power—both economic and political—is now heavily weighted on the side of corporations and industry. And that’s why we’re seeing it being used in many cases to remove jobs. If Amazon could deliver all of its goods by drone it would no doubt be likely to do so, just to get rid of the labor force. Drones don’t go on strike or want to be paid a living wage. That’s a reflection not of technology, but of the balance of power in our society.

Is taking the human element out a bad thing?

It is a bad thing when we’ve got 5 percent unemployment [in the U.K]. When I was a student, the unemployment rate was below 1 percent. We regarded these proposals that it should be allowed to rise to 2 percent as quite outrageous. This is something which for many people, it scarred their lives and particularly the young people. There’s no doubt, but you have to ask why are jobs not being created? Why are they being destroyed? One reason is that we’re not allowing for this element.

Is this shift in power a new phenomenon?

I think there are some parallels that the kind of balance of power we have now is a bit like that at the end of the 19th century, which led to the development of labor unions, government intervention, regulation, and things like the Sherman Act—all designed to constrain industrialists who were exploiting the labor force and their consumers.

Tech is replacing some jobs, but would you agree it can empower the powerless? For example, those who have rallied online against the transatlantic trade agreement?

One can see that with the TTIP. The opposition [in the U.K.] has been largely Internet-based. Groups have been able to contact their representatives in large numbers. I suspect that wouldn’t have happened 10 years ago. We would probably have written to some Member of Parliament and that would have been it. On the other hand, it would be wrong to suppose that is adequate protection, and I think individuals are doing this partly out of a sense of desperation.

The European Union and the U.S are negotiating over this trade deal and the only people consulted are corporations and the government. There’d been no involvement of workers or consumers in these discussions. It was going to be passed without any democratic accountability.

And the average person was able to speak out against that?

Yes, the Internet allowed people to do that. There are Avaaz and 38 Degrees and other bodies that are very effective. We’ve seen it in other cases; it is opening up new potential and particularly with young people. On the other hand, it’s not a replacement organizing politically in an old-fashioned kind of way.

You mention that the inequality gap began to widen in the 1970s and 1980s, depending on the country. That’s roughly when the PC and the Internet began to take off. Is there a connection?

The widening gap in terms of wages actually began in 1950, around the year the first commercial computer was delivered. The wage issue was widening, but other things were headed forth, particularly proposals in taxes and developing the welfare state. I’m not a fan of the view that technology is what’s driving this. I think it was much more political. France had a much lesser increase [in the wage gap], and they had a computer in 1951 as well.

Another example of inequality you mention is that of interest rates—for example, the high interest rates on payday loans used by the poor. What can be done there?

One thing the government can do is go back to allowing people to save in index-linked savings accounts, so you can earn 1 percent plus the rate of inflation—a lot better than you would have earned over the last 10 years in a bank. Ireland does it, as do other countries, so it’s quite possible. There’s nothing against the government providing the three or four banking services that 75 percent of the population wants.

Given the many threats organizations face in protecting critical information and processes, an information security policy is arguably one of the most important documents an organization can create.

Given the many threats organizations face in protecting critical information and processes, an information security policy is arguably one of the most important documents an organization can create.